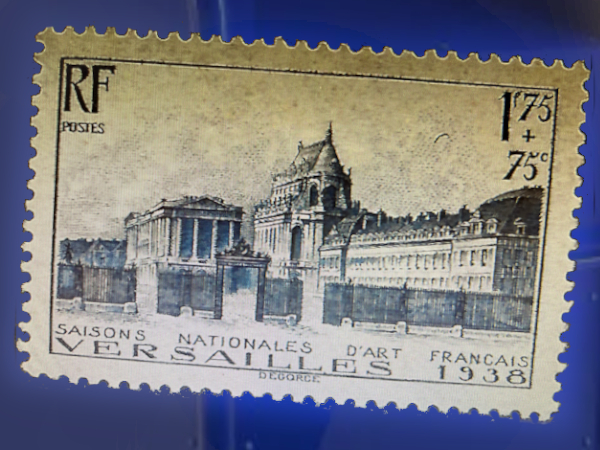

The author's own French, Palace of Versailles 1938 stamp

We stamp collectors are a vanishing species. Most of us who continue to collect, stubbornly unperturbed by the digital tsunami that has all but destroyed the purpose for postage stamps, are in our seventies and eighties. Our hearts wax nostalgic for the days when our mailboxes offered a daily smorgasbord of first-class letters franked with colorful commemoratives, when we traded duplicates, formed neighborhood stamp clubs, visited the local brick-and-mortar stamp store; and when we proudly showed off our collections to admiring friends and family. These days, however, we’re embarrassed to share our collecting activities with younger folks, let alone try to recruit them into the hobby. No matter that many luminaries have been collectors: King George V; President Franklin Roosevelt (he even designed a few); the early twentieth century banker and arts-and-sciences philanthropist William H. Crocker, who helped rebuild San Franscico after the 1906 earthquake. Younger generations may be surprised to learn that John Lennon collected stamps.

But FDR and King George V and even John Lennon lived in a time when people mailed letters via post and stamp collecting was still a widespread hobby and department stores like Gimbel’s and Macy’s included stamp departments. Stamp shops once occupied an entire block on Nassau Street in lower Manhattan. In the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, there were dozens of street-level stamp stores in New York City alone. Today, that number has shrunk to...one: Champion Stamp Co. on West 54th Street, Manhattan.

As for me, I began collecting when I was nine, in 1952. There were no Gimbel’s equivalents in Southwestern L.A. where I grew up, but there was Woolworth’s and Newberry’s and Kress’s Dime Stores, each of which devoted two aisles’ worth of worldwide assortments, albums, hinges for mounting the stamps, bags of so-called unsorted “mystery mixtures.”

Even more fun than buying stamps from dealers was rummaging through dumpsters and relatives’ boxes of letters, scissoring off the stamps and soaking them off the paper. The inevitable duplicates that I would accumulate I used for trading with my collector friends. Sure, I liked physically challenging activities like most kids my age, but they were no match for the sleuthing adventures of stamp collecting.

There: I have just slipped into an acetate mount my mint, never-hinged 1.75 Franc +75 centime semi-postal (i.e., base postage plus a contribution to a particular charity or support organization), issued by France in 1938, depicting the Palace of Versailles. The surcharge was added to benefit the Versailles Concert Society. It’s a beautifully engraved stamp, a miniature work of art like so many postage stamps; but more important is how stamps like this serve as portals to their country’s history and culture. The Versailles semi-postal triggers multiple associations for me, not just about Versailles or its Concert Society, but about the fact that a country finds it worthy to ask its citizens to support such a society by contributing a few additional cents with every stamp purchase. Postage stamps encapsulate, aesthetically as well as pragmatically, what books, museums, and school classrooms amplify. At the same time, a carefully assembled stamp collection can be valuable—not merely as an “investment” like stocks and bonds, but as a legacy to be shared with friends, family, and the philatelic community at large. To collect quality stamps is to archive them in the most protective way possible. Thus, the acetate mounts into which I slip my French semi-postal and similar specimens preserves the stamps’ pristine original gums (“OG” in philatelic notation), prevents soiling and perforation damage—but not color-fading, which is why valuable stamps must not be exposed to direct sunlight.

Before acetate mounts were invented, collectors used glassine hinges to mount mint stamps, and nobody seemed concerned that the resulting hinge mark on the back (leaving a telltale impression on the gum) would detract from its value; but it did, eventually, often by a significant amount. Never hinged (“NH”) mint stamps issued before 1930 became difficult to find, as uncommon as pre-1930 well-centered stamps. Mint stamps with disturbed gum; any stamps with frayed, short, or pulled perforations; smudges, sunning; and even the minutest of creases or tears will dramatically reduce a stamp’s value. Contrarily, perfectly centered, pristine specimens will command prices far above catalogue value. Such stamps are known as condition rarities, or simply gems, and they are often accompanied by a certificate of authenticity from an expertizing agency.

One gazes upon a prized or visually attractive stamp as one gazes upon any other work of art, a painting, or an ancient artifact: the stamp sparks a rich aesthetic response; and when you place hundreds of stamps at your fingertips, your brain becomes a swirling, alchemical brew capable of transporting you to bygone times...

We die-hard collectors are saddened by the discouraging reports on the financial plight of the USPS, which has been incurring annual losses in the billions of dollars. The causes behind such losses are understandable. The major one is the precipitous drop in first-class mail. During the holiday season more people these days prefer to send e-cards. Whatever is most convenient, right? It saves time; it certainly saves money. Fifty dollars’ worth of fine-quality traditional holiday cards (50 cards), plus the postage cost of mailing them at 78 cents a pop ($40) is enough to buy one or two additional gifts.

And yet, the USPS continues to issue postage stamps in abundance. Even though the need for stamps continues to decline more rapidly than the supply, there has not been a proportionate decline in stamp production. Clearly, the USPS is doing all it can to entice people to collect stamps despite their diminished utility. That is why we see so many new issues celebrating icons of popular culture such as muscle cars, Star Wars robots, superheroes, cartoon characters, exotic plants and animals, even skateboards and fishing lures.

I find this troubling. Even though these stamps can be used for postage anytime (the service to be rendered has been prepaid, after all), the fact remains that their secondary purpose as collectibles has become their primary purpose. Postage stamps represent a time when old- fashioned letter-writing on stationery was a part of daily life. That practice has continued into the digital age but is now a mere shadow of what it once was. I keep wondering if there is some way to reverse the mail decline. As a professor of English (now retired) with forty years’ experience teaching writing to undergraduates, I urged my students to write letters by hand. Yes, they rolled their eyes, and after class whipped out their phones and began cheerfully texting. Gone, alas, is the pleasure to be had of shaping words with pen and ink on quality stationery. I am grateful for email (I don’t text—it stifles my writing style), but I try to limit my e-mailing to urgent or practical matters. When writing to friends and family, I prefer to send old-fashioned letters and greeting cards and frank them with any of the thirty or so stamps the U.S.P.S. issues each year, especially their holiday-themed stamps. How many emails, not counting routine work-related correspondence, do you send to folks in a week on average? A dozen? Thirty? Let’s say twenty. That’s well over a thousand emails a year. Imagine if just twenty percent of the U.S. population wrote and mailed via post a thousand letters a year: that’s 1000 x 20% of 350 million (i.e., 1000 x 70 million)—a total of seventy billion letters, which would generate roughly thirty billion dollars a year in revenue from that additional posting of first-class letters. If I am not mistaken, that would represent nearly a 1000% increase over current first-class revenues. This may still not be enough for the USPS to regain solvency, perhaps, but a significant step forward; sufficient, perhaps, to nix proposed draconian measures like stopping Saturday mail delivery or shuttering branch post offices and processing centers. And, more importantly for philately, a renewed foundation, a newly legitimized gold standard, for the postage stamp as an object of intrinsic importance, once again worthy of widespread admiration.

I know, it’s a pipe dream. Stuff for idle nostalgic rumination—and heaven knows what fine nostalgic ruminators we stamp collectors are.

The overwhelming problem, of course, is how to persuade people to write letters the old- fashioned way once again, as well as to become more conscious of regarding stamps for their potential value (not just philatelic market value, mind you, but historical, cultural, and aesthetic value), along with enjoying the experience of franking their letters and greeting cards with commemoratives and rediscovering (or discovering for the first time), the relaxing, intellectually stimulating pursuit of the hobby of philately.

Here is a suggestion, a hail Mary one: Nearly all businesses these days rely on metered postage. Not a problem for USPS revenues, but a let-down for stamp collectors. With so high a percentage of first-class mail these days consisting of business-related correspondence (bills, invoices, policies, mail-in ballots, and so on), think of the greater visibility postage stamps could have if businesses opted for them rather than metering. Yes, yes, efficiency rules. The same time it would take a clerk to affix stamps to a hundred envelopes, a machine could meter ten thousand of them. But surely someone could invent a postage-stamp affixing machine, assuming one doesn’t already exist.

Ironically, the USPS continues to print first-class commemorative stamps in huge quantities —not as large as in pre-Internet / iPhone days, but still larger than the demand for them warrants. That’s because the U.S. Postal Service, a for-profit organization (unlike its pre-1971 government owned predecessor, the U. S. Post Office), caters to collectors (alas, to a fault), which explains the many eye-catching designs and topics. Most collectors, myself included, do not appreciate such excessive collector-catering, other than maintaining a philatelic window at the local post office or not grumbling when a collector asks for certain issues. We certainly do not want the kind of exploitation we see in some Eastern European, Middle Eastern, African, and Latin American countries whereby attractive stamps are produced almost exclusively for collectors and are “cancelled to order” (CTO) as soon as they come off the presses and sold directly to dealers. Many of these issues, while technically valid for postage (un-pre-cancelled, of course) in their home countries are almost never used as such.

So why continue to covet stamp collecting? It isn’t just because rare stamps make good investments (assuming you have acquired expert knowledge about them and have the financial resources to buy them); nor is it because there’s a tiny chance you might stumble upon a rarity affixed to one of your great-grandparent’s love letters; or because kids love stamps for their dazzling variety. It is also because stamps are, simultaneously, pleasure-laden lessons in history, science, and art (in the manner of reproduction as well as in the design itself, also works of art in miniature). Just as important, stamps reflect the culture of the countries that produce them, their values and traditions, and, yes, their political biases; and they do so in visually intriguing ways.

Stamp collecting still occasionally crops up in popular literature. Keller, the hired-killer protagonist of Lawrence Block’s Keller’s Greatest Hits series (Hit Man, Hit List, Hit Parade, etc.) spends his off-hours with his “classical era” (1840-1940) world-wide collection and bidding for stamps in auction houses. Rare stamps have been the subject of several novels1, even a successful Broadway play, Mauritius (2008), by Theresa Rebeck. It saddens me that most people these days do not regard stamp collecting as "popular," and that nearly all the brick-and-mortar stamp stores have vanished in the U.S.2, together with many antiquarian and used bookshops. That’s not a coincidence by the way; book-collecting has also been upended by the digital age.

Two scholarly books closely examine postage stamps in a cultural context, and they both do so from the perspective of semiotics, i.e., postage stamps as sign or symbol systems that embody political, social, and historical views of the respective issuing countries. In European Stamp Design: A Semiotic Approach to Designing Messages (London: Academy Editions, 1995), David Scott, examines the way icons and symbols are used in stamp design to convey a nation’s identity. And in Miniature Messages: The Semiotics and Politics of Latin American Postage Stamps (Duke University Press, 2008), Jack Child limits his scope to the messages conveyed by the designs of stamps issued in Latin American countries, especially in Chile, to compare their representations of the Allende and Pinochet regimes.

Postage stamps, then, disclose a great deal about the issuing country’s values, political and social history, and achievements across the full spectrum of disciplines. In this context, “collecting” stamps means so much more than organizing them into albums; it means to study them as intricate micro-texts, often possessing the complexities of entire books on any given subject.

1Here are five examples: Robert Graves, The Antigua Stamp (1937); E.V. Cunningham, The Case of the One-Penny Orange (1977); Hammond Innes, Solomons Seal (1980) William Tapply, The Dutch Blue Error (1984); Lawrence Sanders, McNally’s Secret (1992); Barry Maitland, The Chalon Heads (1999).

2Paris, however, continues to be a haven for stamp collectors. See my parting reflections

I get annoyed having to give reasons for continuing to collect stamps in the digital age. One shouldn’t need a rationale for pursuing one’s heart’s desire. And yet, at the same time, I can’t resist offering reasons.

Stamps are a sleuth’s dream come true. The many variations that exist among certain issues (especially those printed before 1930)—color, perforation, watermark, design, paper-type—offer fascinating challenges to the serious philatelist. Monographs have been written about, and exhibits devoted to, a single series, even a single stamp, like the world’s first postage stamp, Britain’s 1840 “Penny Black,” because of its numerous varieties. (For example: P.C. Litchfield, Guide Lines to the Penny Black; London: Robson Lowe, Ltd., 1949). It is also possible to collect different types of cancellations, on or off paper, as well as stamps “on cover” (affixed to their original envelopes), so as to highlight provenance, say. In the early days of airmail, for example, “first flights” would be commemorated by a special cachet and or postmark.

There are a couple more reasons for collecting, which are somewhat trickier to explain. One of them has to do with nostalgia for a simpler age, when letter writing played a significant role in the way we communicated with one another, when people enjoyed relaxing with objects of study and aesthetic contemplation. The iconic image of the stamp collector is that of a man or woman seated at his or her desk, magnifying glass in hand, scrutinizing a stamp about to be mounted in an album. There are stamps issued by Monaco and other countries depicting the stamp-collecting British monarch, King George V, and the stamp-collecting American president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in just such a pose.

Another reason is that collecting stamps fosters a contemplative state of mind. The digital age has been taking quite a toll on our collective ability to reflect, to take the time to think deeply about things. We are frazzled by multitasking. Wasn’t technology supposed to give us more time to relax? Instead, it has done the opposite. Our smartphones, iPads, tablets, laptops enable us to work while mobile; indeed, these devices seem to encourage mobility. They also enable us to bring work into our leisure time, our vacations. You can work on your way to work, or work on your way to play, or just break down the distinction between work and play altogether.

And finally, this reason: Philately can even extend to other worlds!

August 2, 1971: Apollo 15 Astronaut David Scott is scurrying about on the lunar surface, getting ready to postmark a letter, the first to be postmarked on another world. It is smudged in the lower left corner with moon dust, obviously from Astronaut Scott’s gloved hand as he applies the postmark, two postmarks actually, one of which cancels the tete-beche 8-cent commemoratives, “United States in Space: A Decade of Achievement.” More than half a century later, you can gaze upon the envelope with its historic postmark in the National Postal Museum in Washington, DC.:

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Aug

2

1971

ON THE MOON

Image courtesy of the National Postal Museum, Smithsonian Institution. © United States Postal Service. Used for editorial purposes.

How delightful that NASA saw it fit to work in this little ritual, to give recognition in such an astonishing way to the cultural significance of mail. Add this to the letter-carrier’s credo, along with not letting bad weather or topography impede mail delivery: “nor interplanetary distances, nor lack of oxygen, nor 250-degree heat, nor lethal solar radiation.” And yes, we have (since 1991), a National Postal Museum (part of the Smithsonian group) devoted to America’s splendid legacy of postal service and postage stamps.

Postage stamps, along with the collecting of them, have become obsolete in the digital age. Funny how that O-word doesn’t seem to apply to collectors of antiques, or of coins (we seldom need coins for purchases these days). I’d love to see an “Antiques Road Show” for stamps. True, there are stamp shows, even some on an international scale, but none are ever televised or even mentioned except in the two philatelic magazines that still exist in the U.S.: The American Philatelist and Linn’s Stamp News. The hobby suffers from bad or (worse) nonexistent press, and collector-pandering by the U.S.P.S. and other stamp issuing agencies. If what was once dubbed the world’s greatest hobby is to be resuscitated—if not to its glory days, then at least to the time when it was widely acknowledged to be a respectable pursuit—here is what should be done:

Stop the exploitation. I’m referring to the printing of CTOs—new issues specifically targeted for collectors by annulling their postage raison d’etre with off-the-press cancellations. Is it not the height of illogic to collect stamps that were never intended for postal use

Integrate stamps into lesson plans. Teachers of all subjects, not just history and geography, should use postage stamps as veritable ambassadors to the topics they depict. Name a subject; there are almost certainly stamps that have been issued somewhere in the world that feature it.

Launch image reversal campaigns. Publicize stamps as cultural icons, as art objects, as potent windows into the cultural life of the issuing country. Depict stamp collectors as youthful, not as candidates for assisted-living communities; as vigorous, not sedate. I recall a U.S.P.S. magazine ad from the 1970s depicting a white-water rafter in action, with the caption, “For adventure he collects stamps.”

Make old-fashioned letter-writing NEW-fashioned, by presenting it as a still-useful form of social media. Letters should be regarded as keepsakes, not as ephemera to be deleted with a single computer key. Stamps used for franking letters should be seen as part of the letter-writing/letter-receiving experience.

When I once asked a friend what she thought of collecting stamps, she said it was one notch below watching paint dry. Philately has failed to attract the interest of anyone under retirement age, despite the efforts of organizations like the American Philatelic Society, and those of the U.S.P.S. in their effort to issue stamps that would appeal to them. Is it conceivable that philately will enjoy a revival, perhaps via some videogame or Hollywood flick?

Blake Edwards’ 1963 mystery-romance film, Charade, is, to my knowledge, the only major motion picture in which the story revolves around stamps. The story is set in Paris, a haven for stamp collectors to this day. In one delightful scene, we follow the Cary Grant character as he wanders, in search of clues that would help him (and his rivals) find a missing fortune, through an open-air stamp market near the Champs Elysées. This venue is a fictional version of the Carré Marigny, which has been in operation since the late nineteenth century. Alas, it no longer bustles with people of all ages as the movie depicts, but is still a happy, energetic place for dealers and collectors to convene. Moreover, the City of Lights hosts several other venues for philatelists, such as the Marché aux Timbres, also near the Champs Elysées; and according to Elaine Sciolinos, in an Oct. 2017 New York Times article (“In Paris, Passion Battles the Decline of Stamp Collecting”) there are thirty stamp shops along the Rue Drouot (9th Arrondissement), and several others in the Passage des Panoramas. New York City today, by contrast, has one street-level stamp shop remaining (Champion Stamp Co., on West 54th Street, Manhattan).

If Paris can still champion philately in the digital age, why can’t the U.S., along with the rest of the world?

Bio-Fragment: Fred White, a professor of English, Emeritus (Santa Clara U), retired thirteen years ago and is still recovering from academ-itis. To aid in his convalescence, he collects wine as well as stamps and tries to stay sober most of the time so he can continue scribbling.