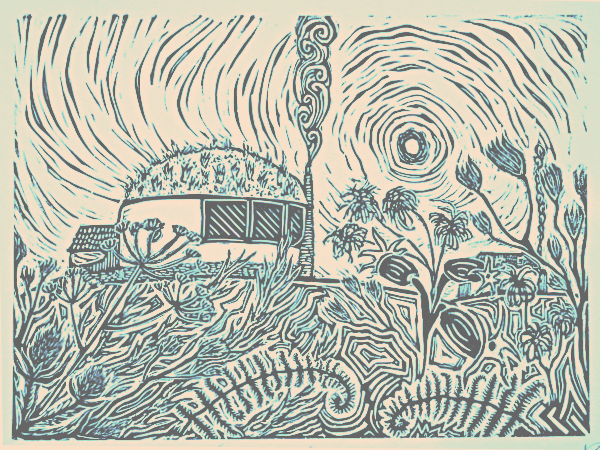

'Refuge', a linocut of the Hobbit House by artist and center chef Kit Spink who works out of a studio in Inverness.

I’ve weathered enough Cape Cod winters to know about the euphoria that rewards the tenacious when the frost breaks. The trees bud and the sands warm, and we discover--as if for the first time--how blue the sky has been all this time. So I could have hunkered down, and wrestled with my own interiority along with my characters. Then I stumbled upon the Moniack Mhor retreat online and decided to take my laptop on a trip to type away beside the wood stoves of the Scottish Highlands instead. I’m glad I did.

Others may choose retreats with spas or yoga, but I find it worthwhile to go outside of my comfort zone—a few hours squashed into a plane—and then enter a new perspective by changing time zones and cultures. As fiction writers and readers, we thrive in immersion and the expanding perspectives that come from experiencing other characters and settings, including those from real life. Plus: focused time on projects is a must.

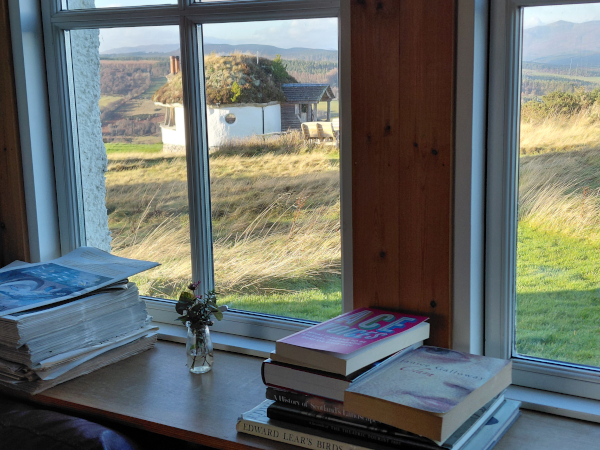

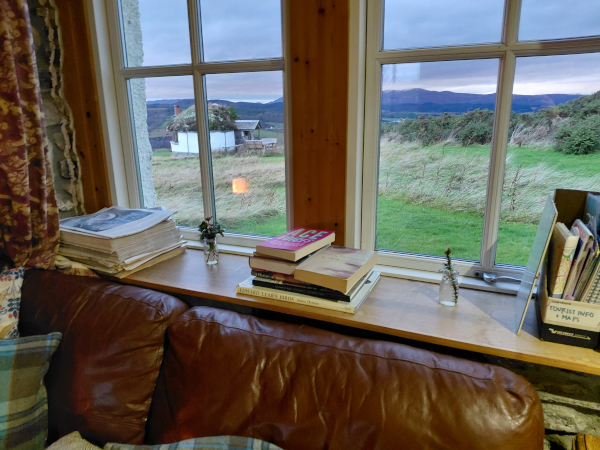

I was delighted to come across the possibility of 5 days at a fiction retreat just north of Inverness (in-ver-NESS) and promptly signed up for the last available spot with two accomplished authors and tutors, Louise Welsh and Zoë Strachan. This was time to spend working on our own projects in converted croft and cattle buildings and the straw-bale ‘Hobbit House’; enjoy a potluck fellowship of writers (most of them Scottish and returners) and brave the restless cinematic weather of the rolling hills during the reduced high latitude daylight hours of 8:30 AM - 3:30 PM in December.

In preparation I read Young Mundo by Douglas Stuart, pulling up blanks in my Kobo dictionary while tapping on unknown words on almost all of the pages. And then I couldn’t help myself from imitating accents on Scottish Tiktok until I worried I wouldn’t be able to stop the knee-jerk habit when faced with IRL attendees. Words like glaikit and numpty and an excessive number of terms for describing what we would call foul weather and endless variations on the comical results of whiskey. Not to mention those that nod to the fun in anything bawdy or vulgur.

The plane reached the moss-colored carpets of treeless mounds, leaving no reference to scale until patches of windmills appeared. Then we descended through low clouds into the dreich, the pour of rain soaking the flat tarmac where even the workers were covered in full rain gear. Unfazed on the adjacent field, intrepid sheep grazed on the sodden green. I asked the first young man in this new-to-me land if this was the shuttle stop—they all know English, right?--and he responded with a guttural baritone that turned on a trill of a burr and that conveyed absolutely no information to me, except that he found something humorous in our interaction. Perhaps it was my bemused face as I stepped back into puddles in my thin-walled gutties (sneakers).

Moniack Mhor is a ‘charity’ funded by the Scottish government. The sense was that we were to contribute to the communal care of the place. It has a full staff (by the end of the stay I was able to discern differences in accents). Kit, the British cook (and linocut artist) provided an abundant first dinner and lunch spread each day and then the twelve of us took turns cooking from menus each night in teams of three. Around 4ish, he would give the team a quick run-down of the equipment and then he and all the staff would abandon us to our own devices. Dinner always went without a hitch (There was a refrigerator stocked with wine).

Each morning started in the dark as we found our way to the big kitchen work table for granola and a big mug of coffee that helped me stave off the time change. Then we were off to write in our rooms or in the common areas by the fire. We all scheduled our own one-on-one sessions with the tutors which were tailored to our own goals, and mine were thoughtful discussions that gave me things to work on before longer follow-ups. I chose to look close at structural connections and tighten arcs and themes--fodder for the rest of the winter.

The Hobbit House

In the middle of the week we had a talk in the Hobbit House with Francis Bickmore, a literary agent who, thankfully, skipped over marketing and shared a contagious love for writing. Interestingly, the round straw-roofed building where we held his talk, like a round table, was egalitarian in design. Where do you seat a special guest in a circle when there’s no hierarchy to the geometry of the room? Near the wood stove, of course.

Each day I bundled up and went for a walk to catch the rapidly changing landscape as winds pushed clouds across the hills and mists rose from valleys. There were magical moments when shafts of sun broke through a cloud over a mountain and highlighted a small piece of a hill or a stand of trees. No wonder of the reverence for the ‘fair folk’ (I won’t risk calling them fairies out of respectful trepidation). First, I always stopped at the top of the hill to visit the hairy coos, the Scottish Highland cow breed, perfectly orange and color-wheel-complementary to the blues of the landscape, as their heads slowly swung their immense sideways horns to take a look at me. Like the hearty double-coated horses to the other side of us, they also were unfazed with the slant of the mucky fields and damp and wind. The farmed venison in the fields above kept their distance and I only heard tell of them.

With Scotland’s rich history (and lack of winter daylight hours) it’s no wonder they have a love for stories told in gatherings around a cherry-red heat source. We had readings on two of the nights. As a 'Merican that speaks in flattened mumbles rather than syllables, I was taken by the musicality and the organic emphasis in their syllables and found myself wondering: would this poem be as pure lovely if I was the one reading it aloud? I missed, perhaps, 20% of what was said, but enjoyed as much as I understood and was glad to be part of the salon-like ceilidh.

Fran, the cook on the last day and long-timer on the staff, guided my team in how to prepare the haggis neeps and tatties, and put together the cranachan, a lovely desert made with rasberries, cream and a little whiskey. It amused me that she asked me to repeat myself as much as I asked her to do the same. She demonstrated that sewer (one who sews) and sore were both clearly two syllable words. I couldn’t help feeling lazy-toned as I listened to her voice climbing over consonants and emphasizing all parts of each word with athletic articulation. Throughout the week I could sense a special place for the upcoming haggis and the pride of the Scots in their traditions. I wasn’t sure about the combination of organ meats but found them quite delicious, made milder as they were with the oats. Not aware of the importance of the gesture and being not worthy (even with Scottish descendants on both sides), I casually delivered the haggis to the head of the long table to the spontaneous clapping of all those seated. Then, the cutting of the haggis commenced while the Scottish members of the cohort took turns reciting passages from Robert Burns’ Address to a Haggis, (1786):

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the puddin-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o’ a grace

As lang’s my arm.