I grew up in a house where professional sports were not an obsession, but baseball held memories tied to that ancient idea of hitting an object with a stick as far as you could. One afternoon, my mother asked if I wanted to meet a famous anthropologist who grew up in our house. No, I replied—I wanted to play baseball.

So much for meeting Margaret Mead.

For forty years, the same group of middle-aged men has gathered for Opening Day at Fenway Park, a ritual that began as simple baseball tradition but has evolved into something more profound—a mirror reflecting how extraordinary moments of small community can illuminate the disparity of conscience.

Our diverse crew represents an America we thought we knew: Charlie, an MIT electrical engineering professor whose season tickets started this tradition, sit in Fenway's cramped seats alongside others some Italian Americans, an African American, Jewish, Agnostic friends from different American origin cities, different financial and educational backgrounds who found common ground and became friends.

Each year begins with breakfast and Bloody Marys at the S&S Restaurant in Cambridge, a family-owned deli that opens early just for our group, before we emerge from isolated New England winters with a renewed promise of shared youthful values, the hope of warmer air and a new season of baseball.

But after 40 years something has shifted. The ceremonial aspects—military presence, flag ceremonies, deafening flyovers, even "Sweet Caroline"—have become increasingly formulaic throwbacks, clinging to an outmoded model of innocence trying too hard to reach for wholesomeness but ending up feeling disengenuous. The pseudo-patriotic display forces uncomfortable questions about what we're really celebrating.

Fenway Opening Day represents more than baseball—it's a re-engagement, and a reminder of Time. Over the decades, we've shared births, graduations, marriages, career changes, and even some losses in our ranks while the game itself becomes secondary to our just being together.

This discomfort crystallized in the aftermath of 2015's Opener. After partying until 2 AM at Charlie's and barely sleeping, I rushed bleary-eyed to catch an 8:00 AM flight to California.

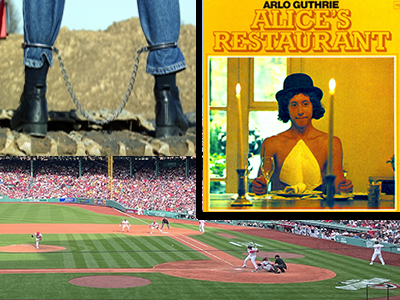

At Logan Airport, I placed my suitcase on the rollers leading to the xray machine. An alarm went off and then a bit of flurry concerning MY bag leading to an absurd chain of events.security found two joints in my suitcase, leading to an absurd chain of events including a perpwalk past the check-in line, being handcuffed to a chainlink fence in the Logan holding tank, leg fetters for a minor infraction.

I immediately imagined the slowmotion steam roller sequence from Austin Powers of me running towards my bag mouthing "NOooo! Out of the foggy-brained morning I momentarily remembered the two joints left inconspicuously in a bag on the top of the suitcase with some of my recording equipment (which set the alarm off in the first place).

The stern, Amazonian State Policewoman with knee-high storm trooper boots and Princess Leia danishes of red hair had found the marijuana cigarettes. She asked my age with my license in hand. I corrected her miscalculation, "No, not 54, 56." She snapped: "Oh, so you want the last word, hunh? Fine." She handcuffed me and perp-walked me past the security line.

In the airport police station, she cuffed one hand to a chainlink fence while searching for my criminal record on what she called a "Ronald Reagan era computer." The absurdity peaked when they put me in leg shackles—for two joints—and put me into the police van.

Seated on my version of what Arlo Guthrie called the "Group W bench," I couldn't escape his "Alice's Restaurant" lyrics echoing in my mind:

"Sargeant, you got a lot a damn gall to ask me if I've rehabilitated myself... I'm sittin here on the Group W bench 'cause you want to know if I'm moral enough to join the Army, burn women, kids, houses and villages after bein' a litterbug."

The parallel was inescapable. Guthrie was arrested for dumping garbage on Thanksgiving; I was arrested for possessing two joints after celebrating Opening Day. Both encounters revealed the same bureaucratic absurdity and disproportionate response to minor infractions, but more importantly, both exposed the machinery of a system that criminalizes the targeted while ignoring larger injustices.

Once we were in that dank, windowless jail I listened to idiotic answers to the "what-are-you-in-for?"stories from the much younger fellow inmates.—where I was the only Caucasian and would be the first released due to inherent bias—I couldn't escape the parallels to Arlo Guthrie's travails in "Alice's Restaurant."

A high-priced lawyer soon escorted me before an exasperated judge who announced, "get this guy out of here, I have serious work to do."

I paid the $100 fine. Within a year, marijuana was legalized in Massachusetts.

The experience haunted me, revealing the gap between the mythic America we celebrate at baseball games and the America that puts people in shackles for victimless crimes.

Years later, during another opener, my teenage son caught a fly ball in our section—a prized souvenir any baseball fan would treasure. Without hesitation, he turned and handed the ball to a little boy sitting in front of him, whose face lit up with pure joy. The crowd erupted in spontaneous applause, recognizing genuine kindness that embodied the best of what we hope to pass on. In that moment, authentic values—generosity, compassion, putting others first—shone through in a way no manufactured ceremony could match.

This is the struggle facing all of us who value conscience over blind compliance. The question isn't whether we want to be political—it's whether we can afford not to be engaged. It about the loss of the common sense of a reasonable society and the scale of bureaucratic inappropriateness.

When ordinary people are criminalized for commonplace behavior, when militarism becomes entertainment, when authority responds to minor infractions with overwhelming force, silence becomes complicity. We have been told this during times of great social upheaval. “Silence = Death,” was a slogan adopted by ActUp surrounding the time of HIV/AIDS.

Early glimpses of the intent of PROJECT 2025’s major reduction in the power of a shared representatitve government in favor of a corrupt authoritarian, the disinformation and distortions from Russia over their invasion of Ukraine, the killing and starvation of children wantonly by IDF in Israel and the starvation of Syrians all justified by calcified fanaticism; the list is endless.

The individualism necessary to stand up against tyranny demands that we evolve beyond personal comfort into the more difficult terrain of an active moral responsibility. Our personal experiences are threads in a larger tapestry when authoritarian overreach touches every community, every family, every person who dares to question or exist outside prescribed boundaries.

Our baseball openers continue, but for me their meaning has evolved. Our digitally addicted era proliferates misinformation and division, tbut hese genuine human gatherings become both more precious and more necessary since Covid set out to separate us. The parallel to sitting in a theatre to watch a film as an audience relies on something more than absorbing the story—it is the watching of it together. laughing or crying with others as opposed to the isolated experience of viewing from a handheld device, it is a shared experience. Remarkably, being in the audience, while seemingly contradictory to the isolation of solo viewing brings you closer to finding commonality in the group. In essence to re-connect with what it means to be a human. So,yes, baseball can bring us together.

These types of gatherings offer the remedy of reaching outside our familiarity, where maintaining our humanity and kindness relies on our capacity for genuine connection, and where moral questioning becomes itself a form of resistance through active curiosity.

Moral imperatives are not about heroism—it's about refusing to let the machinery of oppression operate unopposed. It's about recognizing that the personal is always political, and that our individual choices either enable or resist the systems that would diminish our collective humanity.

The Group "W" bench waits for all of us, in one form or another. The question is whether we'll sit there in silence or find our voice in the chorus of resistance that every generation must sing.