“Sometimes, to be funny, one must lie a little,” so said the Fox in The Little Prince. Playing fast and loose with the facts would also be a fair way to describe my dad’s approach to storytelling—whether the stories were funny or not. And, as many people will tell you, my dad could tell a story. He was talented and smart. Handy. Capable in ways that I could only dream of. But perhaps his most sterling quality—what he was most known for—was his humor. And his ability to tell a damn good story.

To me, some of the funniest stories were times when being a father nearly broke him. Say, the time he took me, a friend, and my older sister up to Boston. On the ride up, there was some banter; There was some (barely) suppressed rage—understandable when your son purposely reflects the sun into your eyes.

Once we arrived in Boston, my sister departed to meet a friend, leaving my dad, my friend, and me to visit a museum. A short while later, I would borrow the car keys, subsequently losing them while chasing birds in a field next to the parking lot. It didn’t make any more sense at the time.

When my dad learned the how and why of my losing the car keys, he was less than thrilled. To put it mildly. My saving grace was that there was company; otherwise, I’m sure he would have absolutely—spectacularly—lost his shit.

After searching for the keys for a bit, Dad decided to regroup, to get lunch, and then resume the search for the keys—or form another plan that didn’t involve murdering his only son.

When we got back from lunch, the car was gone. In our absence, the vehicle had been towed. I’m not sure I could have made him madder if I tried. But again, the saving grace: company. We would spend a good deal of that day walking around, waiting for the spare set of keys sent on a bus from my mom. Dad barely managed the smallest of conversations through gritted teeth, no doubt questioning why he didn’t stop his family at one kid and a cat.

I don’t remember how he told that story, but I’m sure he’d downplay his ire. In fact, some of Dad’s funniest stories needed little embellishment. The type of stories I never got tired of hearing, threading that gossamer line cleaving “funny” and “Dad’s a felon.” There’s the occasion he made up a “magic show” for a roomful of kids he was supposed to be looking after, not letting his lack of magician’s abilities slow him down from performing.

In the course of the magic show, Dad had a kid climb into a trunk to make him “disappear.” He kept the trunk slightly ajar, as he didn’t have the key to unlock it. I’m not sure how he intended the act to go, but it certainly didn’t involve another kid running up and slamming the trunk lid shut. Faster than you can say “statute of limitations,” the kid was sealed inside. Oh, and the parents (who were in a different wing of the building) would be coming to collect their kids in not too long.

While Dad frantically tried to get the trunk open, kids in the room wailed that the kid in the trunk was going to die, which probably didn’t do wonders for Dad’s anxiety. Then again, maybe this gave him that extra push to somehow break open the trunk and avoid manslaughter charges. To say nothing of his ability to get rehired as a babysitter.

The wailing of a death foretold also scared the living shit out of the kid inside the trunk, who was already not having the time of his life. I’m sure part of the story was exaggerated, but to what extent and for what purpose, I can’t fathom. Whatever “light” he had put himself in was about as far from sensible as one can get.

Other stories that required little doctoring were tales from his childhood. Macabre, bizarre, or revolting, they made me laugh the hardest. I respected his ability to admit to such folly, even if I laughed mercilessly at some of his misadventures. Some left me speechless.

The stories speak of a sort of Bart Simpson or Calvin and Hobbes shenanigans—if they were written by someone with a depressive streak.

Like the story about how he and some friends had found a floating brown mass in a pond and had taken turns climbing aboard, jumping from the brown mass into the water. After several turns, they discovered the "brown mass" was a dead horse.

There was the cautionary tale about him and a friend stripping down to their underwear and rolling around in fiberglass insulation like it was cotton candy (if you’re unfamiliar with fiberglass insulation, it’s made of glass fibers). He was too young to know any better, but it’s also true my parents met in a group home, so take from that what you will (to be clear, neither were residents).

Some stories made me laugh so hard I cried. I speak of the time when Dad stuck his mother’s dental dam into his mouth for unknown reasons. When Grandpa Ed discovered Dad, he smacked him on the back of the head, sending the contraceptive flying without a word.

Or the story that raised more questions than I ever got answers to: The time he found human remains in his basement and messed around with them until his mom took them to the dump. As one does.

Unlike some of his stories, I don’t question the integrity of these, as why would someone make up such things? Certainly not because it made them look good.

Yet other stories were subject to a large dose of truth-stretching.

He would often portray himself as more assertive, more brash, and more confident than he ever was in the event in question.

For some context, Dad was a carpenter and a damn good one. And yet, I’ve never seen someone so good at something they seemed to despise every second they spent at it. He was almost unparalleled in his craftsmanship. Meticulous, bringing a perfectionist eye to everything he did—which often led to much furious cursing (no one said perfectionism was relaxing). Thus, when someone compromised his work, it was no surprise that hackles were raised. Perhaps best exemplified by his tale of a boss’s wife who had painted over something Dad had made. Dad, after letting the brownnosers finish cooing over the handiwork, loudly said, “Who painted that piece of shit?” Knowing full well who painted that piece of shit. I’m reasonably sure this was the nuts and bolts of the story. Dad could be quick with a one-liner, but I also know some of this story was subject to “alternative facts.” And the thing is, in Dad’s storytelling oeuvre, he wouldn’t consider this tale as one of his funnier stories. But I think it’s one of his funniest (and not semi-criminal).

Other times, his stories were so embellished it was hard to ascertain—but not impossible to make an educated guess—where the truth stood.

He often told a story about living with his dad and being taught how to fight. At the time of the lesson, according to him, Dad was reading in a chair.

According to him, his dad had come home plastered. Grandpa Ed started to antagonize Dad, even getting physical. Telling him he was going to teach him how to fight. After enough provocation, Dad responded by jumping up and delivering a punch that split his dad’s eyebrow. According to the story I had heard many times, grandpa Ed had wailed, “You’d hit your father!”

Young boys invariably look up to their fathers. We seize on their stories, their tales of heroics, and swell with pride. We retell them with glee. We want to believe our dads have the machismo of a Clint Eastwood. They are, after all, our protectors. They make us feel safe in the most primitive of ways. No one goes around bragging their dad is a coward. So the story also made me swell with a fair bit of pride. After years of asking Dad to retell this story, I asked his father about it.

In Grandpa Ed’s version of events, Dad had been the one who came home stoned and had mouthed off. And Dad had been the one who instigated the fight, possibly sucker-punching his father.

As I listened to the version of events Grandpa Ed told (whose own credibility was murky at best), I stole glances at Dad. He looked furious. But he didn’t, I couldn’t help but notice, argue about the veracity of events. As the rest of my family laughed, Dad fumed.

When I thought about it, Dad’s version of events painted him as not only the innocent but also the hero. Grandpa Ed’s story was a 180 from what I’d heard for years. And somewhere in between, the truth lay.

Some stories took on such a fantastical bent that it would take a real moron to fall for them. When he was a young boy, he was so tiny he once fit in a shoebox and was swept downstream? Who but the most questionably intelligent among us would ever believe that?

In my defense, I was young when Dad told me this. Fourteen at the most. I don’t actually remember how old I was when Dad told me this. But I definitely remember being way too old when I realized that my Dad’s story was complete bullshit.

I don’t totally begrudge Dad for lying to his son to make a good story. We both got something out of it: I was entertained, and he got one over on me.

But time softens people's sharp edges and flattens events. Try as I might, I can’t remember specifically too many stories he told. Much like most of life, what once loomed large eventually fades to a flicker. It’s funny the things you remember and the things you forget.

Dad was revered for his storytelling. They made people laugh. They were often varying degrees of fabrication. But the stories people enjoyed depended on their disposition. And relation to him. If it had schadenfreude, I was a happy camper.

There were times I’d catch snippets of stories he told others. Fantastic stories that revolved around drug use and druggy thinking.

Sometimes he’d let me in on them, especially if the humor wasn’t at his expense. Like the story he told me about taking acid and seeing the Grateful Dead, having a spectacular time but wondering where his best friend was, whom he’d later locate at the far end of the venue, crying to himself.

There are many ways to tell a story, but only a handful of ways to tell them well. Any idiot can tell a story. But like telling a joke, it takes a certain person to pull it off. To keep someone in your grip as you hold the floor. I envied Dad’s ability to hold people in his thrall, even as I recalled the events in question being far different than the version being recounted. This could be downright frustrating at times, as my own role in the story could scarcely resemble my actual behavior or character.

But unless you are in a deposition, integrity has little to do with telling a good story. If anything, it’s a roadblock.

I may not have inherited Dad’s adeptness with mechanical problems (he once made me several science projects that I passed off as my own, almost setting a school record at one point when I shot a pencil down the length of a hallway. In retrospect, no one seemed too alarmed about a kid carrying what looked very much like a crossbow through the school). Nor did I get his carpentry prowess (I’m not bad, but you’d be better off hiring my sister, who seems to have dodged most of the genetic deficiencies I’m saddled with). I definitely didn’t reap his automotive aptitude (I once accidentally electrocuted a mechanic; another time, I locked myself out of my truck, called for help, and re-locked myself out after AAA had just opened it. The mechanic not buying my explanation that the truck “somehow” got locked again).

However, I’d like to think some of his storytelling talent was passed down (along with an ability to get lost in a straight line and a near-pathological incompetence at sports). And if I have any of the “Fox” in me, coloring these pages with my own embellishments, I would claim it’s because of my piss-poor memory rather than an intentional misrepresentation of the facts.

It’s funny when someone dies the things you miss. When I have a practical problem or need advice, I often think of what Dad would say. But when I’m getting to know someone new, I miss Dad’s storytelling. Whether they were works of pure fiction or not, that man could tell a story.

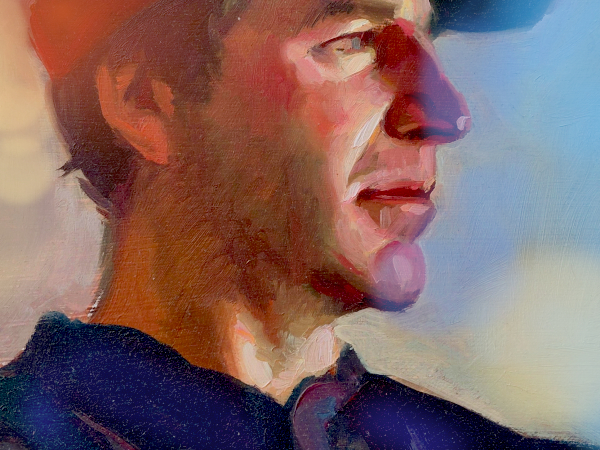

Editor's note: Jack's father Damon was the funniest person I’ll ever know. And the most generous. One time he brought me a lavish bouquet to take to my wife. I assumed he had bought it--he got these random impulses to make a specific person happy--and maybe this time the object of his affection was my wife or it’s possible he wanted to make me look good. The important thing he said to me, and he was adamant: make sure you tell her that you got them for her and, whatever you say, don’t let on that I gave them to you. So I entered the house, arm extended, saying, “I got you flowers,” and the first thing she said was, “Did Damon give you those?”

And we heard the same story about the shoe box that Jack described. But in our version Jack was young, maybe 8 or 9, and the gist was that--since Damon was short--the fact that he could float down a river in a shoebox came from an inherited superpower, like he was born the Moses of short people. The uplifting aspect of the story was that his son’s active imagination was still pliable enough to believe that when his father was a child he was gerbil-sized.

He had a voice that traveled and laid into whatever the subtext of the room was; speaking without restraint causes a stir in New England. Often on first exposure, baffled faces would turn away like, Who is this guy? But I never saw anyone not warm to him within minutes.

Damon died young from the rare and quickly lethal brain tumor, glioblastoma. The person who said, Why does it happen to the good ones? reflected all of our thoughts. While he was sick I noticed a pendant my daughter started wearing and it came from a time, years before, when we had come across a young woman selling used items spread out on the sidewalk as if she needed cash. Without hesitating, Damon gave each of my daughter’s $5 to spend, making all 4 or us and himself happy in the process. Judging from their faces my first thought was, Why don't we all do that? Little things still mean a lot.

I can't help but thinking how chuffed Damon would be to read his son's unfiltered stories, even this one here about himself. Damon used his loud voice to say what the rest of us could only think, much to all of our amusement.